A comprehensive and sometimes surprising portrait of the handling of criminal cases in the United States against individuals identified as international terrorists during the five years after 9/11/01 has emerged from an analysis of hundreds of thousands Justice Department records by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC).

TRAC, a data research organization connected to Syracuse University, has been studying a wide range of federal agencies and programs for more than 15 years.

Among the key findings about the year-by-year enforcement trends in the period were the following:

Figure 1: Click for larger image |

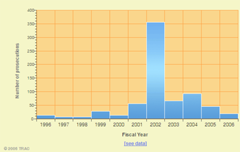

![]() In the twelve months immediately after 9/11, the prosecution of individuals the government classified as international terrorists surged sharply higher than in the previous year. But timely data show that five years later, in the latest available period, the total number of these prosecutions has returned to roughly what they were just before the attacks. Given the widely accepted belief that the threat of terrorism in all parts of the world is much larger today than it was six or seven years ago, the extent of the recent decline in prosecutions is unexpected. See Figure 1 and supporting table.

In the twelve months immediately after 9/11, the prosecution of individuals the government classified as international terrorists surged sharply higher than in the previous year. But timely data show that five years later, in the latest available period, the total number of these prosecutions has returned to roughly what they were just before the attacks. Given the widely accepted belief that the threat of terrorism in all parts of the world is much larger today than it was six or seven years ago, the extent of the recent decline in prosecutions is unexpected. See Figure 1 and supporting table.

Figure 2: Click for larger image |

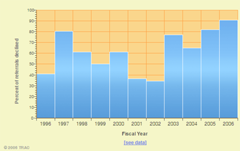

![]() Federal prosecutors by law and custom are authorized to decline cases that are brought to them for prosecution by the investigative agencies. And over the years the prosecutors have used this power to weed out matters that for one reason or another they felt should be dropped. For international terrorism the declination rate has been high, especially in recent years. In fact, timely data show that in the first eight months of FY 2006 the assistant U.S. Attorneys rejected slightly more than nine out of ten of the referrals. Given the assumption that the investigation of international terrorism must be the single most important target area for the FBI and other agencies, the turn-down rate is hard to understand. See Figure 2 and supporting table.

Federal prosecutors by law and custom are authorized to decline cases that are brought to them for prosecution by the investigative agencies. And over the years the prosecutors have used this power to weed out matters that for one reason or another they felt should be dropped. For international terrorism the declination rate has been high, especially in recent years. In fact, timely data show that in the first eight months of FY 2006 the assistant U.S. Attorneys rejected slightly more than nine out of ten of the referrals. Given the assumption that the investigation of international terrorism must be the single most important target area for the FBI and other agencies, the turn-down rate is hard to understand. See Figure 2 and supporting table.

Figure3: Click for larger image |

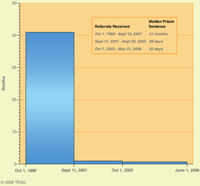

![]() The typical sentences recently imposed on individuals considered to be international terrorists are not impressive. For all those convicted as a result of cases initiated in the two years after 9//11, for example, the median sentence -- half got more and half got less-- was 28 days. For those referrals that came in more recently -- through May 31, 2006 -- the median sentence was 20 days. For cases started in the two year period before the 9/11 attack, the typical sentence was much longer, 41 months. See Figure 3.

The typical sentences recently imposed on individuals considered to be international terrorists are not impressive. For all those convicted as a result of cases initiated in the two years after 9//11, for example, the median sentence -- half got more and half got less-- was 28 days. For those referrals that came in more recently -- through May 31, 2006 -- the median sentence was 20 days. For cases started in the two year period before the 9/11 attack, the typical sentence was much longer, 41 months. See Figure 3.

Recent Background

From what is now known, it appears that well-placed undercover agents and extensive electronic surveillance can largely be credited with the recent apprehension in England of scores of suspects who authorities say were planning to blow up as many as ten airliners on their way to the United States.

These same investigative tools also appear to have been important in uncovering evidence indicating that a Pakistani charity may have been diverting funds originally contributed for earthquake relief to finance the planned terrorism attacks on the jumbo jets. In the United States, as well as England, details about investigations like these leading up to the filing of formal charges are usually not revealed, only occasionally becoming known during trial or as the result of later inquiries.

Essential though the use of secret agents and secret surveillance seems to have been in these related cases, the process now moves from what necessarily is one of the most hidden activities of any government to a much more public stage: the criminal prosecution, trial and sentencing of these suspects.

In the United States, partly because of this country's far more expansive freedom of information laws, quite complete information is available about the actual prosecution of virtually all cases, including those related to terrorism.

| |

This report, based on detailed data obtained by TRAC under the Freedom of Information Act from the Executive Office for United States Attorneys (EOUSA), mostly focuses on the use of the nation's criminal laws in the five years after 9/11/01 against over a thousand individuals who the government had categorized as international terrorists. See sidebar "About the Data".

Fully acknowledging that for a variety of evidentiary reasons terrorism cases are among the most difficult challenges faced by the government, the Justice Department data about the small and declining number of prosecutions and convictions and the resulting sentences for international terrorism raise a host of questions. Among them are the following.

- Despite the highly publicized incidents of actual and threatened terrorism, is it possible that the public understanding about the extent of this problem is in some ways inaccurate or exaggerated?

- How effective are the government's expanding surveillance and intelligence efforts in identifying serious terrorists?

- Once the suspects have been identified, how good a job do the investigators do in obtaining evidence that will result in their conviction in court?

The question of the basic competence of the Bush Administration in managing the overall response of the United States to terrorism has in recent months become a subject of debate for candidates of both parties. And the effectiveness and fairness of criminal enforcement in this area necessarily is a significant part of the whole effort. Several months ago, on June 22, the Bush Administration itself weighed into the discussion directly when the Justice Department issued what it called a "Counterterrorism White Paper." See About the Data for a discussion of the content of the white paper.

The Big Picture

The impact of the events of 9/11/01 on the United States is hard to exaggerate.

Within months, for example, the largest single re-organization of the federal government in more than forty years was underway as the Bush Administration and Congress began shaping the Department of Homeland Security. In the same period, the government and the airline industry agreed to a new program where federal agents would begin screening all passengers for weapons and certain kinds of explosives before they boarded their planes. And under then-secret orders from President Bush, the administration initiated or expanded new surveillance programs by the National Security Agency and the Treasury Department. Meanwhile, Congress began a long struggle to adopt a new body of law intended to profoundly alter the flow of legal and illegal migrants into the U.S. That struggle continues today.

And around the world -- in London and Madrid and Indonesia and Moscow -- terrorists set off powerful explosive devices. In addition to directly affecting all of the living and dying in these cities, the bombings have continued to dominate the evening news broadcasts and the morning papers and the minds of hundreds of millions of people on every continent.

Given the vast world-wide reach of the media, these developments and others have properly become an intricate part of an intense political debate in the United States and in many other countries about how best to deal with these terrifying attacks.

Click for larger image |

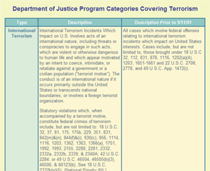

For the federal enforcement agencies, a very extensive effort was launched. As has been previously noted, this report focuses almost entirely on people the Justice Department thought to be international terrorists. But the government has developed a bookkeeping system to track a much broader range of activities concerning several other kinds of "terrorism" as well as what it calls "anti-terrorism." The official Justice Department definition of who is considered an anti-terrorist is elusive. Covered by this term, according to the government manual, are those who have been targeted on the grounds that charging them with any crime might "prevent or disrupt potential or actual terrorists threats." See Justice Department Program Categories. The counts of those tracked by the Justice Department do not include military detainees -- currently numbering more than 400 individuals -- who have been held in the U.S. facility in Guantanamo.

Figure 4: Click for larger image |

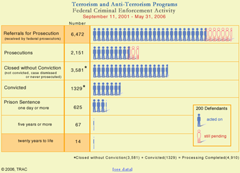

Since 9/11/01 the government has classified a very large number of individuals as either a "terrorists" or "anti-terrorists." The bulk of them, some 6,472 individuals, were referred during the two years following the 9/11 attack. Now five years since the attack, final outcomes have been determined on three out of four of these cases. See Figure 4 and supporting table.

Click for larger image |

For the total set of completions, federal prosecutors decided that nearly two out of three (64%) of them were not worth prosecuting. In addition, for 9% more of the completions, a prosecution was filed but the cases were subsequently dismissed or the individuals found not guilty. Looked at from another perspective, slightly more than one out of four of the total (27%) were convicted. Considered together, this means that five years after 9/11, looking at the 6,472 individuals in the overall count who were initially referred under the terrorist or anti-terrorist programs, only about one in five have been convicted. Details for the specific terrorism and anti-terrorism categories are shown in the adjacent table.

Despite the low success rate in obtaining convictions, the large absolute number of referrals coming from the agencies (nearly 6,500 of them) has resulted in a sizable number of convictions (1,329). For this group it is instructive to consider the penalties that were imposed:

- Only 14 (one percent) received a substantial sentence -- 20 years or more.

- Only 67 (5 percent) received sentences of five or more years.

- Of the 1,329 who were sentenced, 704 received no prison time and an additional 327 received sentences ranging from one day to less than a year.

Zeroing in on International Terrorism Trends

Since shortly after 9/11/01, according to the official Justice Department definition, an international terrorist is an individual suspected of having been involved in acts that are violent or otherwise dangerous to human life which appear motivated by an intent to coerce, intimidate or retaliate against a government or civilian populations. The acts, including threats or conspiracies to engage them, also must be of an international nature and impact on the U.S.

As noted above, in the first eight months of FY 2006, Justice Department EOUSA data show that federal prosecutors filed a variety of different criminal charges against 19 individuals who they had determined met this standard. In the twelve months of the previous year, FY 2005, the Department recorded 46 such prosecutions, only a fraction of the 355 it counted in the year immediately after the attacks.

For some kinds of crime, the number of prosecutions in a given area may be a better measure of official concern about a particular problem than the actual threat. And given the deep public concerns immediately after the attacks, the very large number of international terrorism prosecutions in FY 2002 is hardly surprising. Considering the numerous warning statements from President Bush and other federal officials about the continuing nature of the terrorism threat, however, the gradual decline in these cases since the FY 2002 high point and the high rate at which prosecutors are declining to prosecute terrorism cases raises questions. See earlier table.

The Overall Portrait

Examining the year-by-year changes in government actions provides valuable insights. However, convictions in any one year may reflect investigations that originated at varying points in years past. To examine the impact of 9/11, a useful approach is to collect information about all of the referrals that originated during a set time period, and then follow these cases and examine the resulting outcomes. In this case, TRAC created what is called a "cohort" of all the referrals the Justice Department categorized as international terrorism which originated in the two years following 9/11 and traced what ultimately happened to them through the end of May 2006 (the latest available data).

Figure 5: Click for larger image |

The findings from TRAC's second analysis of this cohort, now followed for almost five years, are as puzzling as those emerging from the year-by-year trends. Among them are the following:

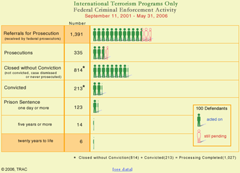

![]() Federal investigative agencies for the whole period referred -- recommended the prosecution -- of 1,391 individuals who the Justice Department classified as international terrorists.

Federal investigative agencies for the whole period referred -- recommended the prosecution -- of 1,391 individuals who the Justice Department classified as international terrorists.

![]() As a result, prosecutions were filed against 335 of these individuals, about one quarter of the total.

As a result, prosecutions were filed against 335 of these individuals, about one quarter of the total.

Click for larger image |

![]() For the whole five-year period, the assistant U.S. Attorneys also declined to prosecute 748 of the international terrorist referrals -- or two out of three during this five year follow-up period.

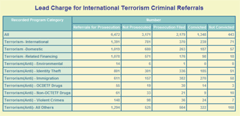

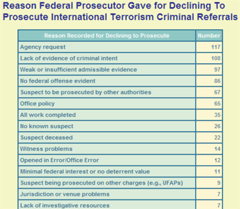

When making a decision to decline, the prosecutors are required to explain why. For more than one third of the declinations, 39% of them, the assistant U.S. Attorneys said their negative decisions were caused by a lack of evidence of criminal intent, weak or insufficient evidence or because no federal offense was evident. Also baffling was the finding that an additional 24% of the referrals were declined as a result of either an agency's request or because of "office policy." See adjacent table.

For the whole five-year period, the assistant U.S. Attorneys also declined to prosecute 748 of the international terrorist referrals -- or two out of three during this five year follow-up period.

When making a decision to decline, the prosecutors are required to explain why. For more than one third of the declinations, 39% of them, the assistant U.S. Attorneys said their negative decisions were caused by a lack of evidence of criminal intent, weak or insufficient evidence or because no federal offense was evident. Also baffling was the finding that an additional 24% of the referrals were declined as a result of either an agency's request or because of "office policy." See adjacent table.

![]() As a result of these various decisions, the government reports that 213 individuals were convicted (by trial or plea) and 123 -- less than one out of ten of the original referrals -- were sentenced to prison.

As a result of these various decisions, the government reports that 213 individuals were convicted (by trial or plea) and 123 -- less than one out of ten of the original referrals -- were sentenced to prison.

![]() After conviction, of course, the judges settle on the actual sentences that will be imposed. In the case of this small number of international terrorists, the sentence was one day or less than a year for 91, one year to five years for 18, five years to 20 years for eight and 20 years to life for six. Ninety received no prison sentence. (As noted above, the median or typical sentence for these 213 individuals -- half got more and half got less -- was 28 days.)

After conviction, of course, the judges settle on the actual sentences that will be imposed. In the case of this small number of international terrorists, the sentence was one day or less than a year for 91, one year to five years for 18, five years to 20 years for eight and 20 years to life for six. Ninety received no prison sentence. (As noted above, the median or typical sentence for these 213 individuals -- half got more and half got less -- was 28 days.)

Lead Charge in International Terrorism Cases

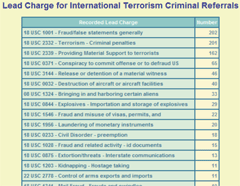

Thus far in this part of the report we have been focusing on the 1,391 individuals who the assistant U.S. Attorneys in the Justice Department had classified as "international terrorists" who were referred for prosecution. Under the department's record keeping procedures, however, a person classified as a terrorist does not have to be charged with crimes that on their face seem to involve "terrorism." Instead, the suspect can be indicted under a wide range of different laws. And in fact, in this case, the department lists about 80 specific crimes that it said were the "lead charge" for these 1,391 accused terrorists. See table.

Click for larger image |

For five of the "international terrorists," for example, the lead charge was 42 USC 0408, a violation of the federal old age, survivors and disability insurance law. And the lead charge for another "international terrorist" was 26 USC 7203, the willful failure to file a return. Some of the lead charges seem more fitting, but are surprising in their rarity. For only one individual judged to be an international terrorist, for example, was the lead charge 18 USC 2381 (treason). And for only two others who were so categorized during the whole five year period was the lead charge 18 USC 0871 (threat against a president and successors).

Here, at the other end of the scale, are the top five lead charges for international terrorism referrals during the post-9/11 years: 18 USC 1001 (fraud/false statements -- 14.5%), 18 USC 2332 (terrorism, criminal penalties -- 14.4%), 18 USC 2339 (providing material support to terrorists -- 11.6%), 18 USC 0371 (conspiracy to commit offense or to defraud US -- 4.7%), 18 USC 3144 (release or detention of a material witness -- 3.3%). In addition, lead charge information is unknown for 17.7% of cases.

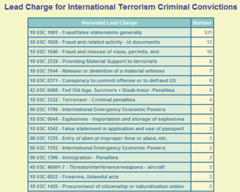

Click for larger image |

The list of recorded lead charge for referrals that resulted in the defendant being convicted of some crime is shorter, but still contains a range of charges. See convictions. Heading the list was 18 USC 1001 (fraud/false statements), representing over half of all convictions -- 56.8%. The rest of the top 4 charges against convicted terrorists were 18 USC 1028 (fraud and related activity - ID documents -- 5.6%), 18 USC 1546 (fraud and misuse of visas, permits -- 4.7%) 18 USC 2339 (providing material support for terrorists -- 3.8%) and 18 USC 3144 (release or detention of material witness -- 3.3%). Two-thirds of all convictions for terrorism involved a fraud or fraud-related lead charge.

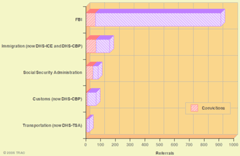

Agency Workload

For each referral, the Justice Department also records the agency that played the lead role in the investigation that led to it. It is not surprising that considerably more than half of the 1,391 referrals for international terrorism -- 913, or nearly two-thirds of them -- were credited to the FBI. See Figure 6 and supporting table.

Figure 6: Click for larger image |

With 161 referrals, the former Immigration and Naturalization Service and later the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) -- now Customs and Border Protection (CBP) along with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) immigration enforcement arms -- was second. Somewhat surprisingly under the umbrella of combating international terrorists, the Social Security Administration, with 84 referrals, was third. And the 70 referrals by former Customs Service now largely CBP was the fourth most active. Fifth -- with 24 referrals -- was the Transportation Security Administration, now in DHS but formerly part of the Transportation Department.

But in addition to the workload, agency-by-agency outcomes for the five year period also can be examined. While the FBI led the federal government in the volume of referrals for criminal prosecution for international terrorists, federal prosecutors declined as not warranting filing charges a much higher proportion of its referrals for prosecution than referrals from most other agencies. Prosecutors filed charges on only 18 percent of FBI referrals and declined to prosecute 82 percent. More of the cases dropped by the wayside at the court stage. This means that less than one out of ten FBI cases disposed of during the five year period resulted in the defendant being convicted for any crime. The median sentence of convictions in FBI cases, although slightly higher than the overall median, was still only 6 months. See table with median prison sentences.

In contrast, it was the Social Security Administration (SSA) which racked up the highest success rate in terms of the proportion federal prosecutors decided to proceed and prosecute in court (92% prosecuted versus 8% declined), and slightly over three out of four (76%) of cases that had reached completion resulted in a conviction. Presumably, the comparatively better record of the SSA was partly related to the fact that its cases were less complex. For the 50 SSA convictions, the median sentence was one month.

The other three agencies -- all now part of the Department of Homeland Security -- had much less success than did the Social Security Administration when judged by either prosecution or conviction rates. Moreover, for convictions from all three DHS agencies, the median sentence was no prison time at all. This means that in over fifty percent of DHS's convictions, the sentences were not even a single day in prison. Details for other agencies are also shown in the accompanying table.

International Terrorism Cases by Federal Judicial District

The separate offices of the United States Attorneys are vital players in the criminal enforcement of federal law. As noted above, the work of federal enforcement as a whole or within these offices can be examined in several ways. One approach is to identify all the referrals that occurred in a specific period of time and then follow the cases in the ensuing years. In this case, for example, the EOUSA data allowed the identification of every international terrorism referral recorded in each of the districts in the two years after 9/11 and the subsequent tracking of them to determine what action, if any, had been taken in regard to each as of May 2006.

The first part of this section examines international terrorism cases in this way and focuses only on the matters that were referred to the prosecutors from September 2001 to September 2003. The second section, just below, presents district-by-district counts for the full five years since 9/11 regardless of when the referral took place. This second comparison, for example, includes referrals received before 9/11/2001 but acted upon after 9/11.

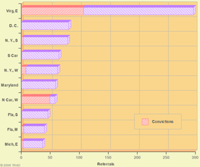

When it comes to the two-year period, the top ten busiest districts are shown in Figure 7, while all districts with any activity are shown in the accompanying table.

Figure 7: Click for larger image |

However, one district -- Eastern Virginia (Alexandria) -- was by a huge margin the government's favorite venue. In this district, located just south of the District of Columbia, the Justice Department recorded receiving somewhat more than a quarter of all referrals -- 297 out of the 1,322 total -- that were finally classified as international terrorism.

The District of Columbia and the Southern District of New York (Manhattan) were the next two busiest districts -- in terms of the number of criminal referrals -- with 82 and 80 respectively. South Carolina and the Western District of New York (Buffalo) had, respectively, 65 and 63 criminal international terrorist referrals.

Many questions are raised by this distribution. The Sixth Amendment of the Constitution, for example, says that:

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence.

Critics note that the heavy concentration of international terrorism referrals in Virginia East strains the principle that defendants should be brought to trial in the district and state where their crime occurred. They also argue that prosecutors favor bringing cases here because the juries in the area near the Pentagon naturally have a large proportion of active and retired military personnel and its circuit court of appeals is among the most conservation in the United States.

|

The data show that Virginia East did prosecute as well as convict a much higher proportion of its criminal international terrorism referrals than was true for most other parts of the country. While nationally 31% of criminal referrals were prosecuted, in Virginia East charges were filed in court on 66%. Similarly, nationally only one in five defendants were ultimately convicted, whereas nearly half (45%) resulted in guilty pleas or verdicts in Virginia East. See district-by-district performance along with convictions by district in earlier Figure 7.

In contrast, the District of Columbia and the Southern District of New York (Manhattan) -- ranked second and third in terms of the volume of referrals -- turned in disappointing outcomes. D.C. had not a single conviction, and in seven out of eight of the referrals the prosecutor declined to prosecute at all. Prosecutors in Manhattan declined to prosecute 83% of the time, and less than 5 percent were ultimately convicted of any crime. And of the 3 that were convicted, two received no prison time. However, even in the much higher volume (107) convictions in Virginia East, the median prison sentence -- half got less, half more -- was only 1 month.

|

For the full five-year period a somewhat different picture emerges. Because of new government withholding, it is no longer possible to obtain information on referrals since September 2003. Thus, it is not possible to examine district-by-district performance in the same way as was done earlier. Prosecution, declination, and conviction counts can be examined. In terms of these indicators of activity levels, because of the wider scope of coverage which extends to cases that began before 9/11, counts are somewhat higher. However, the same districts that were active before are active in this more encompassing list. And as before, the Eastern District of Virginia far and away leads the country. See district-by-district activity table.

Further details on each case can be obtained using TRAC's online query service at

| TRAC Spotlight |

Earlier TRAC Terrorism Reports:

| December 2001

| December 2003

|