The mix of criminal prosecutions now being brought by the Justice Department that Judge Michael B. Mukasey will lead if confirmed as attorney general is very different from what it was when President Bush came to the White House almost seven years ago.

Evidence of the profound and often unannounced changes in the basic thrust of federal enforcement under the Bush Administration has emerged from the records of hundreds of thousands of individual criminal cases that are routinely collected by the government and then analyzed by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC).

Other evidence, drawn from Justice Department budget submissions to Congress, indicate that some of these dramatic shifts will continue at least until after the next administration comes to power in early 2009.

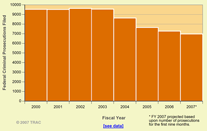

Figure 1. Click for larger image. |

Here are a few selected enforcement trends based on the timely information collected by the Justice Department's Executive Office for United States Attorneys:

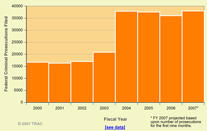

![]() The prosecution of all kinds of white-collar criminals is down by 27% since FY 2000, before President Bush came to office. See Figure 1.

The prosecution of all kinds of white-collar criminals is down by 27% since FY 2000, before President Bush came to office. See Figure 1.

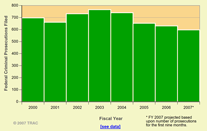

Figure 2. Click for larger image. |

![]() Also substantially down were federal prosecutions against individuals the government accused of various kinds of official corruption. They dropped in the same period by 14%. See Figure 2.

Also substantially down were federal prosecutions against individuals the government accused of various kinds of official corruption. They dropped in the same period by 14%. See Figure 2.

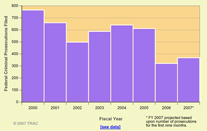

![]() Charges against organized crime figures were slightly up in the last year, but their number currently is about half (48%) of what it was in FY 2000. See Figure 3.

Charges against organized crime figures were slightly up in the last year, but their number currently is about half (48%) of what it was in FY 2000. See Figure 3.

Figure 3. Click for larger image. |

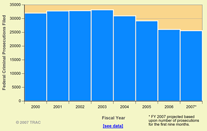

![]() While the decline in federal filings against drug violators was less precipitous, such prosecutions were still 20% below where they were a decade ago. See Figure 4. (While weapon prosecutions grew in the first three years of the Bush administration, since FY 2004 they also have fallen 21%. See table.)

While the decline in federal filings against drug violators was less precipitous, such prosecutions were still 20% below where they were a decade ago. See Figure 4. (While weapon prosecutions grew in the first three years of the Bush administration, since FY 2004 they also have fallen 21%. See table.)

Figure 4. Click for larger image. |

The drop was even more pronounced for drug and weapons cases where the FBI was the lead investigative agency. For drugs, the number of such prosecutions credited to the bureau dropped from 5,014 in FY 2000 to 2,414 in FY 2006. Based on the first nine months of FY 2007, these prosecutions appear to be continuing to drop — down to an estimated 2,332 — less than half of the 2000 total. FBI weapons prosecutions are down around 30 percent over this same period.

Figure 5. Click for larger image. |

![]() The only major enforcement area where federal prosecutions were sharply higher is immigration, where the number of individuals charged with criminal offenses has undergone a 127% jump. See Figure 5.

The only major enforcement area where federal prosecutions were sharply higher is immigration, where the number of individuals charged with criminal offenses has undergone a 127% jump. See Figure 5.

The data thus document that there have been revolutionary changes in the long-established enforcement priorities of the federal government. While new administrations have always had the authority to alter the emphasis they give to different areas, the possible impacts of such shifts — on the lives of individual Americans and the economy — can be significant. This is true partly because local and state agencies are generally not equipped to deal with the activities of organized crime gangs, white collar criminals, international drug dealers and corrupt government officials.

Looking Ahead

While the case-by-case enforcement data highlight the dramatic changes of the recent past, submissions to Congress by the FBI provide evidence that at least some of these changes probably will continue in the near future.

The signal that further declines are highly likely in the prosecution of matters not connected to terrorism — such as white collar crime and official corruption — comes from the most recent staffing request submitted by the FBI in the Justice Department's FY 2008 budget. The FBI historically has played a major role in the investigations of these kinds of crimes. In FY 2006, the agency unit (now called "Criminal Enterprises and Federal Crimes" (CEFC) decision unit) that "comprises all headquarters and field programs that support the FBI's criminal investigative mission" had 12,595 permanent positions. In FY 2008, assuming Congress accepts the administration's proposal, the number of positions in this unit will decline by 14.3% to 10,800 positions. Declining staff almost certainly means declining enforcement. See budget submission, p. 4-110.

Figure 6. Click for larger image. |

An even more dramatic insight into current FBI priorities — strongly focused on intelligence and terrorism work — can be found in the distribution of funds outlined in the FY 2008 budget submission. Here are the numbers: 60% ($3,838 million) for all intelligence/counterterrorism work, 33% ($2,131 million) for criminal law enforcement and 7% ($463 million) for state and local assistance. See Figure 6 and budget submission, Exhibit B.

The distribution of special agents, support staff and others among bureau sub-agencies offers a parallel indicator. But because the FBI has undergone several major reorganizations since 9/11/01 and the key functions sometimes have been re-named, such comparisons are not exact.

Figure 7. Click for larger image. |

With this caution in mind, however, a TRAC report posted in 2002 found that as of 9/11/01 only a small proportion (15%) of all FBI agents — 1,664 out of 11,028 — were assigned to what was then called "counterterrorism." See Figure 7. By comparison, the FBI "positions" assigned to intelligence, counterterrorism and counterintelligence now made up more than half (56%) of the total — 16,486 of 29,373 positions. See budget submission, Exhibit B.

While the distribution of agents within the bureau thus has been substantially altered, the DOJ's FY 2008 budget proposal calls for 11,868 agents, only a slight increase from the total of 11,028 in 9/11. Thus, this redirection of FBI efforts has occurred during a period when total FBI staffing as well as staffing within other DOJ agencies have grown only modestly. See table.

Implications of these Trends?

The overall impact of this shift in resources and concomitant decline in many areas of criminal prosecutions is not clear. But according to explanatory text in the FBI budget document, the potential consequences of this dramatic drop could undermine efforts to root out corrupt government officials all over the United States, to maintain a healthy national economy, to assure honest elections and to deal with other such problems. This is because the detection and prosecution and convictions of corrupt officials, crooked business executives and shady political operatives are thought to be key to deterring such criminal activities in the future.

The FBI statement about importance of investigating all kinds of financial crime, for example, was sweeping.

"In the United States, citizens and businesses lose billions of dollars each year to criminals engaged in non-violent fraudulent enterprises. The globalization of economic and financial systems, advancement of technology, decline in corporate and individual ethics and the sophistication of criminal organizations have resulted in annual increases in the number of illegal acts characterized by deceit, concealment and violations of trust."

But the investigation of financial crimes was not the only area where the FBI described its role as critical. For public corruption and government fraud, the agency's budget document said, it was "the only law enforcement agency primarily charged with investigating legislative, executive, judicial and significant law enforcement corruption." With a possible nod to the upcoming national elections, the statement also noted that the FBI was alone in targeting federal campaign finance violations, ballot fraud, obstruction of justice matters and Foreign Corruption Practices Act (FCPA) violations.