During the most recent quarter (January-March 2012), Immigration Courts issued 2,429 fewer deportation orders[1] than in the previous quarter (October-December 2011). The proportion of cases resulting in an ordered deportation also fell slightly to only 64.1 percent. Thus, in over a third of all cases, the individual was allowed — as least temporarily — to remain in this country.

In most respects the latest figures mark a continuation of the historic drop in deportation orders reported by TRAC in February. This change was touched off last August when the Administration initiated a review of its nearly 300,000 court case backlog. The stated goal of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) review was to better prioritize and reduce the backup of pending matters that had led to lengthy delays in the Immigration Court proceedings of noncitizens the agency wanted to deport. To achieve this longer term objective, ICE attorneys assisted by others had been redirected in a crash effort — part of the prosecutorial discretion (PD) initiative — to review all 300,000 cases to prioritize which to focus on. A consequent drop in overall case dispositions has occurred while these reviews were being carried out.

Details on the change that has taken place nationally during the last nine months are shown in Table 1. These results are from an analysis of case-by-case Immigration Court records obtained from the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) at Syracuse University under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).

Overall court dispositions last quarter fell to 50,489 — the lowest level seen since 2002. (These are preliminary figures and are likely to rise slightly once late reports are recorded.) Regular closures numbered 48,134; the remaining cases (2,335) were closed under the PD initiative.

|

Table 1. Immigration Court Closures by Type of Outcome

* Subtotal for those allowed to stay in U.S. includes a small number of miscellaneous closures not separately tabulated. ** Fiscal year 2012 current through March 28, 2012; the overall volume of closures may increase somewhat since late reports are not yet reflected in these numbers. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Not only did the number of deportation orders fall, but so did court orders granting relief — such as asylum, withholding of removal, etc. Last quarter grants of relief numbered 7,132, down from 9,612 the previous quarter and 8,540 in the same period a year ago.

Administrative closures while much smaller in number (4,350) were up significantly, both because of an apparent rise in regular closures of this type, as well as from 1,801 closures under the PD initiative. (See Table 1.) For an analysis of the closures under the PD program see TRAC's April 19, 2012 report.

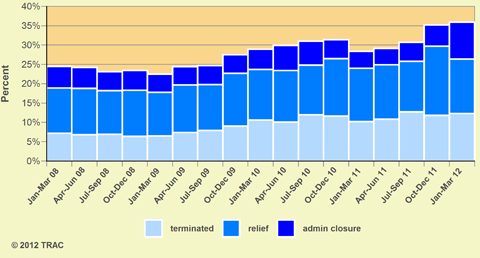

Another way of looking at these numbers is in percentage terms, tracking the percentage of closures in which individuals were allowed to remain — at least temporarily — in this country rather than be deported. Figure 1 tracks quarterly trends over the last four years. The sharp rise in administrative closures this past quarter is clearly evident in the graph. (For earlier time periods, see this chart from TRAC's immigration report of November 9, 2010.)

Figure 1. Percent of ICE Immigration Court Filings for Deportation Orders Not Granted, by Quarter. (Click for details) |

Can the Immigration Court Backlog Be Tamed?

The challenge of taming the growing Immigration Court backlog during a period of fiscal austerity is readily evident in the figures from last quarter. Faced with a large and growing Immigration Court backlog and little prospect of obtaining more budgetary resources, ICE initiated a review of all pending court matters with the goal of winnowing these down to better focus on high priority cases. Through the exercise of prosecutorial discretion, low priority cases would be dismissed or administratively closed.

This special case review resulted in 2,335 closures this past quarter, and 254 during the previous quarter. However, these numbers were dwarfed by the overall drop in number of court closures, even after including these discretionary closures. For example, in a normal January-March quarter, Immigration Courts nationwide disposed of an average of around 60,000 cases — much higher than the 50,489 that occurred this past quarter[2] (see table). Case closures also slipped the previous quarter compared with numbers for the same period in prior years. This drop in case closures overall has apparently been caused by the diversion of staff time devoted to the review, and by the disruption of regular court proceedings.

While discretionary disclosures no doubt will continue to rise, it remains an open question whether their numbers will rise sufficiently to make up for the sizable drop off in ordinary court closures as a result of the dislocations caused by the review process itself. Already, new partial suspensions of court hearings in seven additional cities stretching into July have been announced as ICE's review process continues. Thus, below normal closures in regular court proceedings appear likely to continue. Yet the goal of this initiative was not to reduce case completions, but to increase closures by weeding out low priority cases.

Despite concomitant declines in new court filings, the Immigration Court backlog has continued to rise. The latest figures show that the backlog reached 305,556 last month, a new all-time high.

Full details of the growing backlog — by charge, state, nationality, Immigration Court and hearing location — can be viewed in TRAC's backlog application, now updated with data through March 28, 2012.

Can Better Targeting Reduce the Backlog?

The prosecutorial discretion initiative also includes efforts to better target new cases that ICE files in Immigration Court. Refocusing efforts in a large bureaucracy takes time and energy. To the extent the review process combined with other actions the agency is taking help the agency refocus its targeting efforts on noncitizens with serious criminal convictions and individuals who pose clearer public safety or national security threats, the agency may also find that it is more successful in obtaining deportation orders.

In a 2010 report titled "ICE Seeks to Deport the Wrong People," TRAC found a "significant and increasing proportion of [ICE] cases" rejected by judges who found the individuals were entitled to remain in this country. Deportation orders nationally failed to be granted in at least one out of every four cases ICE brought, and the proportion was rising. In some parts of the country the majority of cases were being turned down. In contrast, in criminal immigration prosecutions the typical conviction rate is 96 percent, even though the government bears a higher burden of proof. And, unlike in Immigration Court proceedings, persons criminally charged are entitled to representation at government expense.

Thus, better targeting in cases brought to Immigration Court could have a significant impact. Over time the same number of court dispositions could actually translate into more deportations if a higher proportion of ICE's filings were successful. Further, because cases in which ICE is unsuccessful tend to consume a disproportionate amount of the court's time, better targeting also could result in increasing the pace and thus the volume of court-ordered deportations. Other things equal, this could begin to bring down the Immigration Court backlog.

The growing Immigration Court backlog is not a recent problem, and it won't be quickly erased. The backlog has been steadily growing since at least 2005. One important origin for the problem was the failure — largely during the Bush Administration — to fill vacant and newly-funded Immigration Judge positions. Government filings seeking deportation orders increased between FY 2001 and FY 2008 by 30 percent while the number of Immigration Judges on the bench saw little increase and for some periods actually fell (see earlier TRAC report). Subsequent hiring of more judges to fill these vacancies during the Obama presidency has not been sufficient to handle the cases that await attention.

[1]Figures for the most recent quarter are preliminary and likely to change somewhat when late reports are included. The term "deportation" is used in a generic sense — whether legally labeled as removal, deportation, or expulsion based upon inadmissibility grounds. Further, under the heading deportation we have also counted orders of voluntary departure. See glossary.

[2] Excluded in these counts are closures where a case is simply transferred from one court to another or there is a change in venue.