Syracuse, NY — The number of prosecutions of federal cases classified by the Justice Department as weapons violations in FY 2012 was almost exactly the same as it was a decade earlier in FY 2002. But within this period, according to an analysis of timely government data obtained by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), there have been considerable enforcement shifts, both up and down.

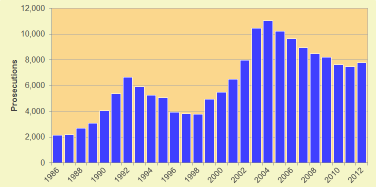

Looking at just the last decade, the records show that from FY 2002 to FY 2004 prosecutions jumped from 7,948 to 11,015, up by more than a third (38.6%). From the 2004 high, however, prosecutions declined to 7,465 in FY 2011, down by 32.2 percent. Then, in just the last year, prosecutions increased up to 7,774, or 4.1 percent higher than in the previous year.But examined over the last quarter century, a somewhat different picture emerges. Despite the recent ups and downs, federal prosecutions today are a great deal higher than in the pre-9/11 era. Figure 1 shows that the volume of federal gun prosecutions has in fact had two distinct peaks of activity. The earlier peak occurred precisely twenty years ago, in FY 1992.

State and Local Gun Arrests Dwarf Federal Actions

In the aftermath of December's 2012 shootings of 20 children and six adults at the Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut, the national debate over the need for new gun laws has become much more intense. President Obama and some Democrats have pushed for possible legislative changes, while the National Rifle Association (NRA) and others contend that, rather than passing a range of new laws, the nation should toughen the enforcement of existing ones.

The most recent call for action on the gun issue came towards the end of the president's State of the Union message. Addressing several gun control measures currently before Congress, Mr. Obama stated:

"The families of Newtown deserve a vote. The families of Aurora deserve a vote. The families of Oak Creek, and Tucson, and Blacksburg, and the countless other communities ripped open by gun violence — they deserve a simple vote."

The president's emotional plea came two weeks after Wayne LaPierre, executive vice president of the NRA, restated his position in testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee:

"[W]e need to enforce the thousands of gun laws that are currently on the books," he told the committee. "Prosecuting criminals who misuse firearms works," he contended. "Unfortunately, we've seen a dramatic collapse in federal gun prosecutions in recent years."

Measuring the total number of such prosecutions throughout the nation, however, is very difficult. This is in large part because the burden of bringing weapons violators to court is thought to fall much more heavily on the thousands of local police departments and prosecutors than the much smaller number federal agencies and U.S. Attorneys. But here, because the statistics collected by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) focus on city, county and state arrests rather than than prosecutions, determining exactly how many gun cases are actually brought to court throughout the country is very difficult.

In its latest report, for example, the FBI estimated that while there were a total of 12.4 million arrests for all causes in 2011, only 153,519 of them involved what it called "weapons, carrying, possessing, etc." This number did not include the large number of additional violent crimes which may have involved a gun. And, as just noted, the FBI statistical report does not cover the number of local prosecutions that resulted from local arrests.

One thing, however, is clear even from these limited numbers. Because of the very different number of the enforcers and prosecutors working at the two levels, state and local gun prosecutions almost certainly dwarf anything that is done by the federal government.

What Kinds of Gun Violations Are Federally Prosecuted?

There are in fact numerous overlaps in the situations where gun crimes can be prosecuted by either state or local law enforcement or the federal government. Sometimes the decision of which jurisdiction — state or federal — will prosecute a gun offense depends upon the specifics of the laws, including which one calls for a longer prison sentence. Indeed, Justice Department records show that at least one in ten federal weapon prosecutions last year were referred by joint federal, state, and local task forces or by state and local authorities.

(In a perverse way, by having relatively weak gun laws, local jurisdictions can divert some cases to federal prosecutors and thereby offload the costs of prosecution and incarceration from taxpayers in that community to all taxpayers across the United States. This is true regardless of whether or not that was the original intent.)

There is a long list of gun offenses that qualify as a federal criminal offense. Most of these are found in the U.S. Criminal Code (Title 18) under Sections 922 and 924. The U.S. Tax Code (Title 26) also has some criminal weapons provisions, largely under Section 5861. Table 1 at the end of this report lists the criminal provisions under these three statutes, along with the number of times each provision was recorded as the lead charge in a federal prosecution during the last five years.

According to these Justice Department data, the most commonly used federal provision is the unlawful shipment, transfer, receipt, or possession of a weapon by a felon (18 USC 922g1). Unlawful possession by a person with mental restrictions (18 USC 922g4), or subject to a court order (18 USC 922g8) are also federal crimes. Other specific provisions outlaw the use or carrying of a firearm during a crime of violence or drug trafficking offense (18 USC 924c). False or fictitious statements in order to acquire a firearm or ammunition (18 USC 922a6), or having false firearm records (18 USC 924a1A) are also federal crimes. See Table 1.

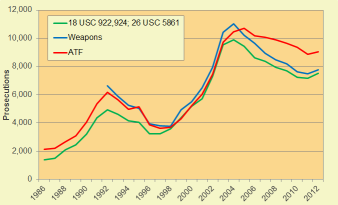

Figure 2: Federal Criminal Prosecutions Referred

by the ATF and by Program and Lead Charge

(Click for larger view and details)

Figure 2 also shows the number of prosecutions where the case was referred by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) — the lead investigative federal agency in gun enforcement[1]. The trend line for ATF shows a very similar pattern to the trend lines tracking prosecutions by lead charge.

Looking at the last decade, the reasons for changing trends — prosecutions sharply up, prosecutions sharply down, prosecutions increasing in the last year — is not clear. The changes, however, do not appear to closely track with the number of federal investigators. For the ATF, for example, employment data from the Office of Personal Management indicate a modest staffing increase from 4,688 in FY 2002[2] to 5,152 in FY 2010 — an increase of 9.9 percent. Then ATF staffing declined by 7.2 percent during the last two years, down to 4,781 employees by the end of FY 2012.

How Often Do Federal Prosecutors Turn Down Gun Cases?

Under law and longstanding custom, assistant U.S. Attorneys have for many years had the power to reject or decline to prosecute selected cases referred to them by the agencies. For weapons cases, for example, the Justice Department data indicate that in FY 2002 the prosecutors rejected 38 percent of all referrals. The declination rate in 2012 was somewhat lower, 32 percent of the total.

There is a wide variety of reasons why matters are declined. Of the 3,741 weapons referrals to U.S. Attorney offices that were closed without further action during FY 2012 by federal prosecutors, about four out of ten files indicated that the there was "weak or insufficient admissible evidence," "lack of evidence of criminal intent," "no federal offense evidence," or some similar evidentiary problem. In an additional two out of ten of the rejected matters, the data said the case did not meet the "office" or "petite" policy, that there was "minimal federal interest" or lacked "deterrent value," or that the agency itself had requested the case be closed. An additional two out of ten were declined for the reason that the "suspect [was] to be prosecuted by other authorities," or a similar such reason. Only about four percent were terminated because there was a "lack of investigative" or "lack of prosecutive resources."

Another possible indicator of the basic quality of the weapons cases is the resulting median or typical sentence that is imposed each year on the thousands of convicted individuals. During the three year period FY 2003 - FY 2005, when weapons prosecutions peaked at over 10,000 each year, the median or typical prison sentence was 46 months. Last year, after some modest annual shifts and fewer prosecutions, the median sentence still was 46 months.

| Lead Charge | Fiscal Year | Total | ||||

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | ||

| All prosecutions with lead charges under 18 USC 922, 924 or 26 USC 5861 | 7,936 | 7,703 | 7,237 | 7,164 | 7,520 | 37,560 |

| 18 USC 922a1A - Unlawfully engaging in the business of firearms | 150 | 117 | 162 | 182 | 172 | 783 |

| 18 USC 922a1B - Unlawfully engaging in the business of ammunition | 3 | 1 | 4 | |||

| 18 USC 922a2 - Unlawful transfer to another by a licensee | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | ||

| 18 USC 922a3 - Unlawful interstate transfer or receipt of a firearm | 4 | 9 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 31 |

| 18 USC 922a4 - Unlawful interstate transfer of any destructive device, machine gun | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 12 |

| 18 USC 922a5 - Unlawful transfer of firearm to one who resides out-of-state | 9 | 8 | 9 | 12 | 6 | 44 |

| 18 USC 922a6 - False/Fictitious statements in order to acquire a firearm/ammunition | 201 | 135 | 123 | 143 | 170 | 772 |

| 18 USC 922a8 - Unlw sale/delivery of armor piercing ammunition by an importer or mfg. | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| 18 USC 922a9 - Unlawful receipt of a firearm by one does not reside in any state | 3 | 1 | 4 | |||

| 18 USC 922b1 - Unlawful sale or delivery of a firearm to a juvenile | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||

| 18 USC 922b2 - Unlawful sale or delivery in violation of state law | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 18 USC 922b3 - Unlawful sale or delivery to an out of state resident | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 10 | |

| 18 USC 922b4 - Unlawful sale or delivery of a destructive device, machine gun | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 18 USC 922b5 - Unlawful sale or delivery without proper record keeping | 4 | 3 | 9 | 16 | ||

| 18 USC 922c - Unlawful sale to a person who does not appear in person | 3 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 16 |

| 18 USC 922d1 - Unlawful sale to a felon or one under felony indictment | 60 | 30 | 44 | 35 | 29 | 198 |

| 18 USC 922d3 - Unlawful sale to a drug addict | 1 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 18 USC 922d5A - Unlawful sale to an alien who is unlawfully in the United States | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 11 |

| 18 USC 922d8 - Unlawful sale to person subject to a court order | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| 18 USC 922d9 - Unlawful sale to person convicted of misdemeanor domestic violence | 4 | 3 | 3 | 10 | ||

| 18 USC 922e - Unlawful use of common/contract carrier to ship firearm or ammunition | 8 | 11 | 15 | 7 | 7 | 48 |

| 18 USC 922f1 - Unlawful shipment by carrier knowing shipment was in violation of law | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 18 USC 922f2 - Unlawful shipment by carrier for failure to obtain an acknowledgment | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 18 USC 922g1 - Unlawful shipment, transfer, receipt, or possession by a felon | 5,617 | 5,671 | 5,310 | 5,211 | 5,487 | 27,296 |

| 18 USC 922g2 - Unlawful shipment, transfer, receipt, or possession by a fugitive | 8 | 8 | 7 | 12 | 10 | 45 |

| 18 USC 922g3 - Unlawful shipment, transfer, receipt, or possession by a drug addict | 146 | 112 | 105 | 109 | 118 | 590 |

| 18 USC 922g4 - Unlawful possession by a person with mental restrictions | 12 | 7 | 9 | 16 | 7 | 51 |

| 18 USC 922g5A - Unlawful possession by an Alien unlawfully in the United States | 293 | 341 | 357 | 376 | 321 | 1,688 |

| 18 USC 922g5B - Unlawful possession by Alien admitted to U.S. under non-immigrant visa | 18 | 18 | 23 | 20 | 16 | 95 |

| 18 USC 922g6 - Unlawful possession by person dishonorably discharged from Armed Force | 2 | 2 | 1 | 12 | 10 | 27 |

| 18 USC 922g8 - Unlawful possession by a person subject to a court order | 29 | 25 | 34 | 16 | 33 | 137 |

| 18 USC 922g9 - Unlaw possession by person convicted of misdemeanor domestic violence | 67 | 49 | 56 | 40 | 32 | 244 |

| 18 USC 922h1 - Receive/possess/transport firearm in or affecting interstate commerce | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| 18 USC 922i - Transportation or shipment of a stolen firearm or ammunition | 8 | 10 | 5 | 6 | 11 | 40 |

| 18 USC 922j - Receipt or possession of a stolen firearm and ammunition | 140 | 152 | 113 | 116 | 101 | 622 |

| 18 USC 922k - Unlawful receipt/possession of firearm with obliterated serial number | 39 | 40 | 34 | 36 | 54 | 203 |

| 18 USC 922l - Unlawful transportation or receipt of imported firearm | 1 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 11 |

| 18 USC 922m - False entry of statements by a licensee | 4 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 17 |

| 18 USC 922n - Unlawful transportation or receipt by a person under felony indictment | 14 | 19 | 18 | 26 | 33 | 110 |

| 18 USC 922o1 - Unlawful possession of a machine gun | 26 | 28 | 36 | 42 | 83 | 215 |

| 18 USC 922q2A - Unlawful possession of a firearm in a school zone | 5 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 31 |

| 18 USC 922s - Interim Brady violation by a licensee | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 18 USC 922t - Violation of national instant check system by a licensee | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 18 USC 922u - Theft from a licensee inventory | 42 | 34 | 30 | 30 | 34 | 170 |

| 18 USC 922w1 - Unlawful possess/transfer of large capacity ammunition feeding device | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | ||

| 18 USC 922x1A - Unlawful sale or delivery to a juvenile of a handgun | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | ||

| 18 USC 922x1B - Unlawful sale or delivery to a juvenile of ammunition for a handgun | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 18 USC 922x2A - Unlawful possession by a juvenile of a handgun | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 18 USC 922 - subsection not specified | 215 | 25 | 3 | 243 | ||

| 18 USC 924a1A - False Firearm Records | 89 | 120 | 122 | 132 | 188 | 651 |

| 18 USC 924a1C - Knowingly import/bring in US or have possession of firearm/ammunition | 1 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 14 | |

| 18 USC 924a3 - A False statement or representation by a licensee in required records | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 9 | |

| 18 USC 924a3A - False statement or representation by a licensee in required records | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 18 USC 924b - Knowing felony to be committed transports/receives firearm or ammun | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 14 |

| 18 USC 924c - Use/carry of firearm during crime of violence/drug trafficking offense | 434 | 325 | 29 | 62 | 2 | 852 |

| 18 USC 924c1Ai - Use/carry/possess firearm during commission federal crime of violence | 69 | 291 | 225 | 321 | 906 | |

| 18 USC 924c1Aii - Brandishing a firearm during commission of a federal crime of violence | 10 | 13 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 71 |

| 18 USC 924c1Aiii - Discharge a firearm during commission of a federal crime of violence | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 22 | |

| 18 USC 924d - Firearms forfeiture | 2 | 12 | 5 | 10 | 29 | |

| 18 USC 924g - Interstate/foreign travel to acquire firearm to engage in crim offense | 5 | 13 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 31 |

| 18 USC 924h - Transfer of firearm knowing the firearm will be used to commit a crime | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | ||

| 18 USC 924j - Violates Section 924(c) and causes the death of a person | 5 | 6 | 5 | 33 | 14 | 63 |

| 18 USC 924l - Stealing a firearm which is moving in interstate or foreign commerce | 4 | 11 | 1 | 16 | ||

| 18 USC 924m - Stealing a firearm from license importer/manufacturer/dealer/collector | 1 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 19 | |

| 18 USC 924o - Conspiracy to commit a violation of 924(c) | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 19 |

| 18 USC 924 - subsection not specified | 26 | 1 | 27 | |||

| 26 USC 5861a - Engage in business of mfg/importer/dealer of firearms w/o proper tax | 1 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 12 | |

| 26 USC 5861b - Receive or possess firearm transferred in violation of Title 26, Ch.53 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 9 | |

| 26 USC 5861c - Receive or possess a firearm made in violation of Title 26, Ch.53 | 6 | 10 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 37 |

| 26 USC 5861d - Receive/possess firearm not register in National Firearm Registration | 129 | 148 | 119 | 122 | 100 | 618 |

| 26 USC 5861e - Transfer of a firearm in violation of Title 26, Ch. 53 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 21 | |

| 26 USC 5861f - Making a firearm in violation of Title 26, Ch. 53 | 6 | 3 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 26 |

| 26 USC 5861g - Obliterate, remove, change, or alter the serial number of a firearm | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 26 USC 5861h - Receive/possess firearm having serial no. obliterated/removed/altered | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||

| 26 USC 5861i - Receive or possess firearm which is not identified by serial number | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||

| 26 USC 5861k - Receive or possess firearm which has been imported or brought into US | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 26 USC 5861l - Make a false entry on application/return/record required to be kept | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| 26 USC 5861 - subsection not specified | 57 | 56 | 52 | 47 | 35 | 247 |

[1] Now part of the Justice Department, up until 2003 the ATF was part of the Treasury Department. The Homeland Security bill transferred most of the agency to DOJ, leaving the tax and trade functions with Treasury in a new Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau. The FBI and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) also get involved in weapons cases, but ATF is the dominant player. Last year, more than three out of four (76.3%) prosecutions labeled weapons cases by the DOJ were recorded as having been referred for federal prosecution by the ATF. The FBI was the second most frequently cited lead investigative agency with 8.5 percent, while DHS with 3.9 percent was third.

[2] For comparability, the figures for 2002 when ATF was still part of Treasury were adjusted to remove the size of the unit that remained in Treasury when ATF was transferred to DOJ.