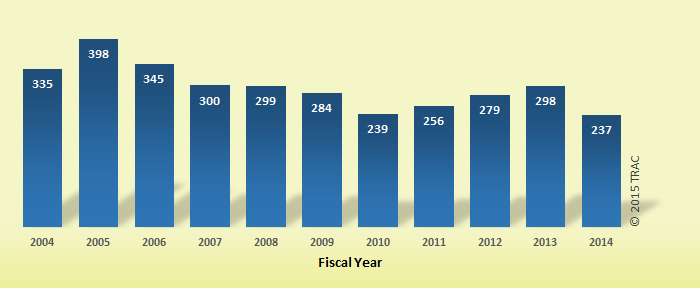

Justice Department Data Reveal 29 Percent Drop

in Criminal Prosecutions of Corporations

| Fiscal Year | Number |

|---|---|

| 2004 | 335 |

| 2005 | 398 |

| 2006 | 345 |

| 2007 | 300 |

| 2008 | 299 |

| 2009 | 284 |

| 2010 | 239 |

| 2011 | 256 |

| 2012 | 279 |

| 2013 | 298 |

| 2014 | 237 |

| Percent Change, FY 2004 to 2014 | -29.3% |

Despite repeated claims to the contrary by top officials at the U.S. Department of Justice, the government's criminal prosecution of corporate violators has declined substantially in the last decade, falling by almost one third (29%) between FY 2004 and FY 2014 (see Figure 1 and Table 1).

This finding is based on a new analysis by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) of hundreds of thousands of individual records developed and collected by the Justice Department in this period. The case-by-case records were obtained by TRAC as the result of a 17-year litigation effort under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).

Source: U.S. Department of Justice; corporations include businesses and organizations.

Official statements bragging about government efforts to combat corporate crime — often issued after the latest major business scandal has made the news — have been a regular feature of the Washington scene for many years.

"For my colleagues and me — at every level of the Department of Justice — instilling in others an expectation that there will be tough enforcement of all applicable laws is an essential ingredient to ensuring that corporate actors weigh their incentives properly — and do not ignore massive risks in blind pursuit of profit," Eric Holder, then the attorney general, said in a sweeping speech to the New York University Law School in September of 2014.

How Are the Annual Counts Determined?

The records cited in this report documenting the decline in the prosecution and conviction of corporations for a decade or more were drawn from two large data systems — one maintained by the Department of Justice and the second by a unit of the federal courts, the U.S. Sentencing Commission. Read more...

Just one year later, Deputy Attorney General Sally Quillian Yates delivered another wide-ranging speech about corporate enforcement at the NYU Law School. While focusing on a somewhat different question than Holder had, Yates said that in most basic ways corporate misconduct "isn't all that different from everything DOJ investigates and prosecutes. Crime is crime," she said adding it was the obligation of the department to hold "lawbreakers accountable regardless of whether they commit their crime on the street corner or in the boardroom."

Earlier, in March of 2013, Michael J. Bresnickat, the director of President Obama's Financial Fraud Enforcement Task Force, made much the same case in a speech to the Washington conference of state bank supervisors. The task force, Bresnickat said, had been formed in 2009 "with the understanding that no matter the office of office or agency — federal, state, or local; law enforcement or regulatory — all of us within government share a common desire and have a core obligation to do everything we can to protect the American public from the often devastating effects of financial fraud, whether it be mortgage fraud or investment fraud, grant or procurement fraud, consumer fraud or fraud in lending."

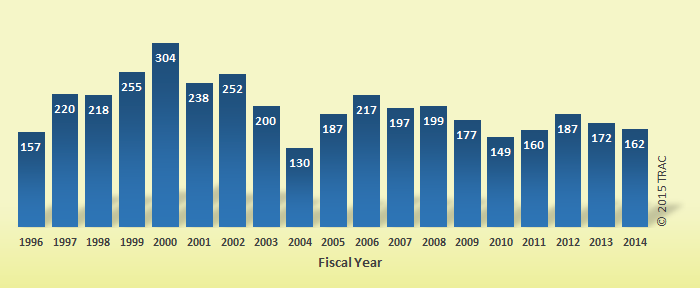

FY 1996 - 2014

|

|

FBI directors also have repeatedly emphasized the importance of the bureau's investigations that focus on corporate crime. Most recently, in a March 12, 2015 statement to the Senate Appropriations Committee, current bureau director James B. Comey named "corporate fraud" as one of eight serious "threats and challenges" facing the American people and law enforcement.

But as documented in the key finding cited above, the government in many ways seems to be moving in a different direction, with the Justice Department's own data providing strong evidence about the extraordinarily small and declining number of corporate prosecutions. Parallel records from a second independent record keeper, the U.S. Sentencing Commission, show similar trends on convictions to those revealed by the Justice Department (see Figure 2 and the sidebar "How Are the Annual Counts Determined?")

Source: U.S. Sentencing Commission; corporations include businesses and organizations.

While the Justice Department was provided an advanced summary of the key findings in this report, it declined to comment.

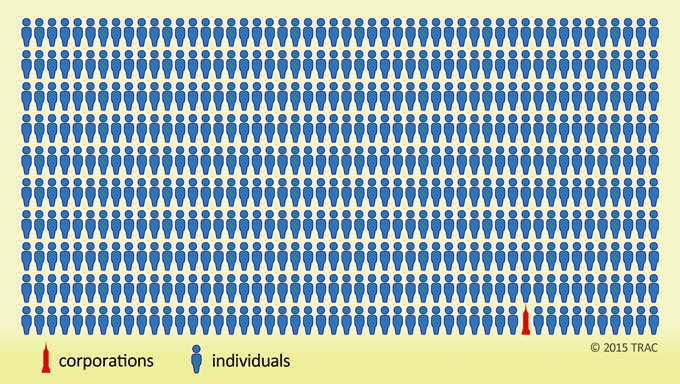

Are Corporate Criminals Rare?

While the data in Table 1 and Table 2 — developed from records obtained from the Justice Department and the federal courts — clearly document a decline in corporate prosecutions, neither table illustrates just how unusual it is for corporations to be pursued for criminal wrongdoing. Over the FY 2004 - 2014 period, Justice Department records show a total of more than 1.6 million defendants were criminally prosecuted. Fully 99.8 percent of these prosecutions were aimed at individuals; only two tenths of one percent (0.2%) — or one in 500 — involved companies (see Figure 3).

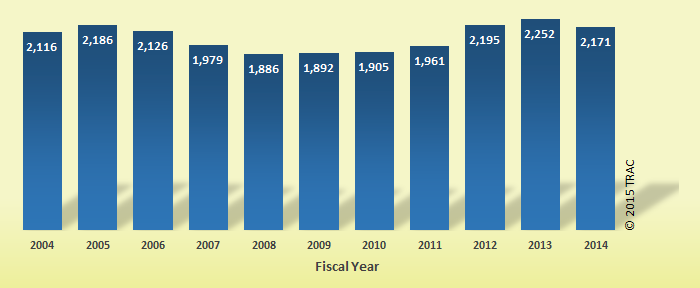

| Fiscal Year | Number |

|---|---|

| 2004 | 2,116 |

| 2005 | 2,186 |

| 2006 | 2,126 |

| 2007 | 1,979 |

| 2008 | 1,886 |

| 2009 | 1,892 |

| 2010 | 1,905 |

| 2011 | 1,961 |

| 2012 | 2,195 |

| 2013 | 2,252 |

| 2014 | 2,171 |

| Percent Change, FY 2004 to 2014 | 2.6% |

Turning to a second but related question: does this tiny number perhaps reflect the high integrity of the business community? Unfortunately no one can answer this question because government and university statisticians have never been able to devise a reliable way to measure the extent of white collar crime and whether it is going up or down.

One thing that can be measured is the number of referrals of corporations to federal prosecutors. As shown in Table 3 and Figure 4 these numbers dwarf the number of actual prosecutions. During FY 2004 there were 6.3 times more referrals for corporate crime than prosecutions. But by FY 2014 the difference between the two measures had grown and there were 9.2 times more referrals than prosecutions.

Source: U.S. Department of Justice; corporations include businesses and organizations.

Meanwhile, the number of such referrals has not been declining. Indeed, there has been remarkable stability in the number of times each year federal investigators referred corporations for prosecution. Such referrals actually increased 2.6 percent from FY 2004 to FY 2014.

Another thing that can be measured is the number of functioning corporations that might be tempted to break the law and whether their total is increasing or declining. According to the latest data compiled by the IRS for the tax years 2002 to 2012, the number of corporations (including partnerships and sole proprietorships and LLCs) was substantially higher in 2012 than it was in 2002, up by about one quarter or 24 percent.

| Type of Business | Tax Year | Percent Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 2012 | ||

| Total | 26,434,293 | 32,783,232 | 24.0% |

| Corporations | 5,266,607 | 5,840,821 | 10.9% |

| C-Corp | 2,100,074 | 1,617,739 | -23.0% |

| 1120-RIC/REIT | 12,156 | 17,630 | 45.0% |

| S-Corp | 3,154,377 | 4,205,452 | 33.3% |

| Partnerships | 2,242,169 | 3,388,561 | 51.1% |

| General | 841,299 | 583,007 | -30.7% |

| Limited | 454,741 | 406,716 | -10.6% |

| LLC | 946,130 | 2,211,353 | 133.7% |

| Sole Proprietorships (nonfarm) | 18,925,517 | 23,553,850 | 24.5% |

Why Are Corporate Prosecutions So Rare and What Explains Their Decline?

In a very large and complex organization like the Justice Department there frequently are multiple explanations for the real differences that often exist between official statements and official performance. This is particularly true when it comes to the Justice Department's current policies concerning the filing of criminal charges against large corporations. A key event feeding the Department's long-term concern on this subject was the collapse of the giant accounting firm Arthur B. Anderson after it was charged with obstruction of justice in March of 2002.

Yet it wasn't until 2008 that the department replaced a previous and heavily criticized policy with a detailed 21-page statement, the "Principles of Federal Prosecution of Business Organizations." The document, written by Mark Filip who was the Deputy Attorney General at the time, begins with a sweeping claim that "the prosecution of corporate crime is a high priority for the Department of Justice." The Filip policy was sent to all United States Attorneys and DOJ department component heads under cover of an August 28, 2008 memorandum.

But this broad mandate about how federal prosecutors should investigate, charge and prosecute corporate crimes is considerably modified when it comes to specifics. The document advises prosecutors to consider the "corporate context" when filing a case against a corporation and to "take into account the possible substantial consequences to a corporation's employees,investors, pensioners and customers" many of whom may have played no role in the criminal conduct, have been unaware of it or have been unable to prevent it." In addition, Filip said, the prosecutors should take into consideration "the non-penal sanctions that may come with a criminal charge" such as a potential suspension or disbarment from bidding on lucrative government contracts.

"Ultimately," the guidelines say, "the appropriateness of a criminal charge against a large corporation must be evaluated in a pragmatic way that produces a fair outcome."

It is highly likely that the 2008 policy directive was central to the mid-September 2015 decision of the Justice Department not to bring immediate criminal charges against General Motors (GM), whose flawed and long hidden ignition system problem had over a decade played a role in the death of at least 124 individuals.

Instead, GM was required to pay a $900 million penalty. And the two parties worked out what is called a Deferred Prosecution Agreement (DPA). Under this agreement, the possible charges of wire fraud and scheming to conceal information from federal regulators would be put off for three years providing that the corporation took a number of substantial administrative reform steps. One was the hiring and paying of an independent monitor to assist in the creation of a compliance program to review the effectiveness of GM's internal control measures.

In defending itself against those who argued that the failure to prosecute GM under the DPA was wrong because it failed to recognize the criminal culpability of the corporation, the prosecutors emphasized the company's remediation efforts such as the creation of a compensation fund for the victims.

(Speaking on a background basis, one highly experienced federal prosecutor said he did not recall a similar "collateral consequences" memo advising prosecutors when considering the indictment of a bank robber or car thief.)

A comparison of agency referrals and Justice Department prosecutions in the five years before and after the new Filip policy was issued appears to indicate its genuine significance in changing how federal prosecutors dealt with corporate crime. While the investigators like the FBI and the IRS kept churning out their referrals for the entire ten year period, data from both the Executive Office for U.S. Attorneys (EOUSA) and USSC show that after the issuance of the Filip guidelines the prosecution of corporations fell. According to EOUSA records, there were 21.9 percent fewer corporate prosecution totals for the five years after the new guidelines than there were for the comparable period before they were announced. Similarly, USSC data show a decline in corporate convictions of 14.9 percent (see Table 5).

| Before and After Comparison* | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| FY 2004 to FY 2008 | FY 2010 to FY 2014 | Percent Change | |

| Referrals to Federal Prosecutors | 10,293 | 10,484 | 1.9% |

| Prosecutions Filed by Federal Prosecutors | 1,677 | 1,309 | -21.9% |

| Convictions (USSC) | 800 | 681 | -14.9% |

Is the decline in corporate prosecutions a stand-alone situation or does it perhaps reflect a general decline in federal prosecution efforts? Overall federal criminal prosecution activity is in fact up, not down. In addition to charting "corporate" prosecutions, the Justice Department keeps track of the far larger number of criminal charges that it brings against individuals. From FY 2004 through FY 2014, for example, the broad prosecution of all individuals has grown by more than a quarter, in large part because of the much more aggressive criminal enforcement of the immigration laws.

But the story is different for one segment, individuals classified by the Justice Department as white collar criminals. Here, according to a recent study by TRAC, prosecutions have dropped by more than a third (36.8%).

It would seem reasonable that the use of deferred prosecution agreements — similar to the one recently reached with GM — might explain aspects of the FY 2004 - 2014 decline in the number of corporations charged with criminal violations. However, a 2014 attempt by University of Virginia law professor Brandon L. Garrett to obtain information about the agreements turned up information suggesting they were relatively few in number. Through a painstaking search of individual Justice Department press releases, news articles and other sources, Garrett said in his book, "Too Big to Jail," that he was able to obtain specific information on about only 255 of the corporate/government agreements from 2001 and 2012 — an average of a little more than twenty a year. Available counts from other sources such as George Mason University Law & Economics Center and Gibson Dunn as well as updated information from Garrett covering 2013 and 2014 again show that these agreements[1] appear insufficient in volume to account for the observed declines in corporate prosecutions.

Conclusion

The officially stated goals of most organizations in the United States are ambitious and high minded. So two central questions can fairly be asked: is the agency in question achieving its stated objectives and if not, why not? The Justice Department's own records make it clear that when it comes to criminal enforcement against corporate violators the agency is falling far short of its goals. What is far harder to determine is why. To resolve that second question would require a well-functioning and principled oversight system operated by the administration itself, Congress, the news media, public interest groups and others — all under pressure from an informed public. But given the current national mood, this clearly is a tall order.

Footnote

[1] Unlike non-prosecution agreements (NPAs), deferred prosecution agreements (DPAs) are presumably already included in corporate prosecution counts since the agreement is entered into after a prosecution is filed in court. But whether annual corporate prosecution totals are adjusted by adding just NPAs or both DPAs and NPAs, their reported numbers are much too small to account for the observed declines in corporate prosecutions during the FY 2004 - 2014 period examined here.